What future did the “Russian Nostradamus” monk Abel predict for Russia

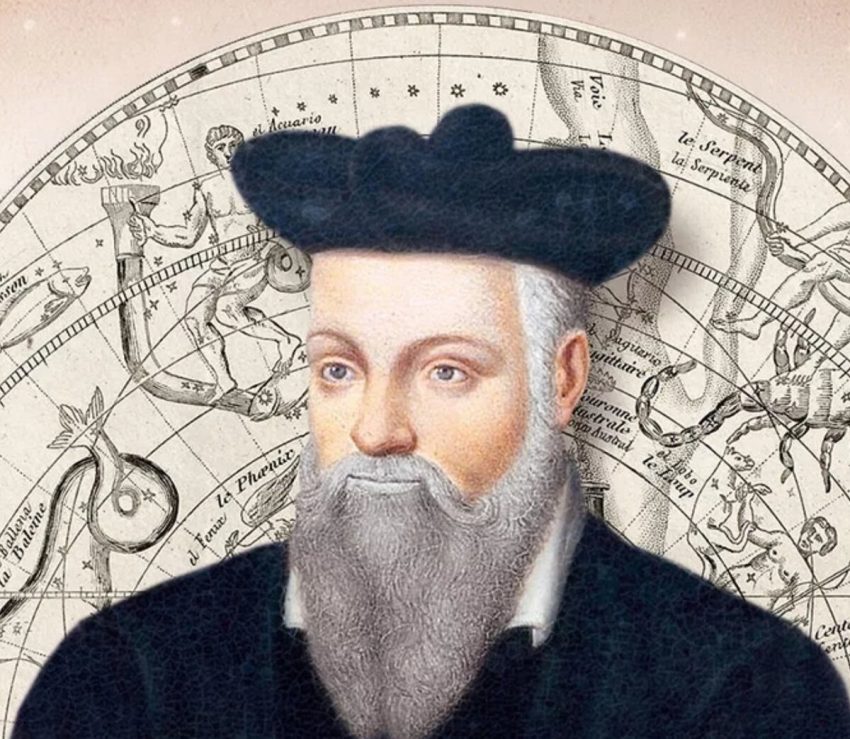

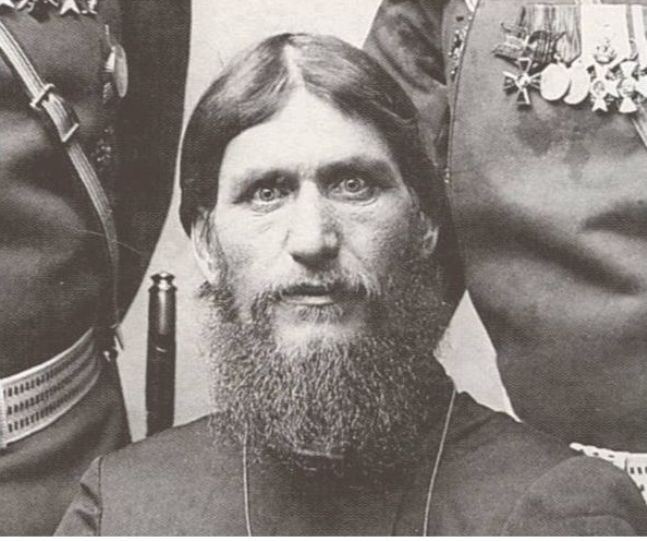

The predictions of the monk Abel about the future of Russia, which he made two centuries ago, still haunt both historians and ordinary people. However, it is unclear whether the mysterious old man actually lived or not.

Did the monk Abel really exist?

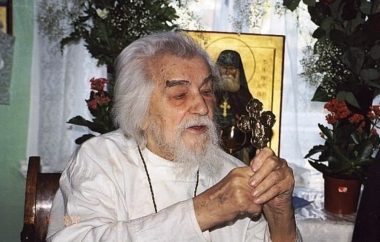

The version accepted by historians says that Vasily Vasilyev (namely, that was the name of the old man) was born in the outback of Akulovo, Tula province in 1757.

In 1785, with the permission of the master, he leaves the village and goes to the monastery. Soon Vasily took monastic vows under the name Abel.

An unknown force forces Abel to go wandering around Russia. Nine years later, he finds refuge in the Nikolo-Babaevsky Monastery. It was there that he created his first book of prophecies. After reading the predictions, Catherine the Great ordered the monk to be imprisoned for many years.

Only after the death of Paul I, Abel was released. The legendary old man passed away in 1841. After himself, he left a couple of books with predictions, for example, describing the subsequent events of 1917.

Vladimirs were also mentioned in them, who changed or will change Russia in different ways.

“Two have already left. The first in the service were heroes. The second was born on one day, but celebrated on another. The third bears the mark of fate. In it lies the salvation and happiness of the Russian people.

It is not difficult to assume that Vladimir the Great had “heroes” in the service. Lenin had two birthdays.

What the monk Abel predicted for the Russian monarchy

On that morning of March 11, 1901, fervent laughter resounded at the windows of the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo. The day before, Tsar Nicholas II informed his servants about a strange find in the Gatchina Palace. In one of the rooms they found a door leading to a secret room, and in it was a chest.

The mysterious chest was hidden by Emperor Paul, who ordered the contents of the box to be opened a century after his death. No one knew what he was hiding in himself. He appeared after the emperor’s trip to the prison of Abel.

Paul I called that day the most fateful day in his life and in the history of the Romanov dynasty.

It is believed that the mysterious old man, imprisoned in the Shlisselburg fortress, told the autocrat the fate of his descendants up to Nicholas II. And she was not easy.

Emperor Pavel Petrovich was so impressed by his prediction that he wrote down and sealed them, leaving behind a note with the order to open the casket in a century.

The secret of the casket of Pavel Petrovich, which was told by the monk Abel

The secret prediction became well known, and the monk himself was dubbed the “Russian Nostradamus.” And no one dared to question the existence of the mysterious casket.

In reality, there was no chest. There was no envelope either. And on that day, the emperor was too far from the Alexander Palace. Also, this episode is not mentioned in the memoirs of Empress Maria Geringer, which are referred to by many adherents of this hoax.

And with regard to Abel himself, not everything is so transparent. Mentions of him are recorded in various sources, but not all of them are reliable.

How the myth of Russian Nostradamus was debunked

The researchers note that many of the “prophecies” of the monk Abel are obviously written down after the fact.

An example is the prophecy about the fate of the last Russian emperor. They appeared only in the 1930s, when only the lazy did not compose fables about the tragedy of the Romanov family.

The same is observed in Abel’s “prediction” about the Great Patriotic War of 1812. It appeared in the public domain half a century after these events.

However, it is known that the personality of Abel was quite popular in high society. And Alexander Golitsyn was called his behind-the-scenes patron. Historians explain this fact by the count’s hobbies of mysticism.

Researchers are sure that the “Russian Nostradamus” is a painfully loud name for Abel, but his personality was still outstanding, if only because he inspired fear in the sovereigns themselves.