Canadian economists have calculated the date of death of mankind

Humanity may die as early as 2290, economists at the Canadian research company BCA have calculated. In theory, this means that investors have less reason to save money and more reason to invest in risky assets.

Mankind may have only a few centuries left to live – an extremely short period in the scale of the history of human existence, which has about 3 million years, follows from the report of the Canadian company BCA Research, which specializes in investment research.

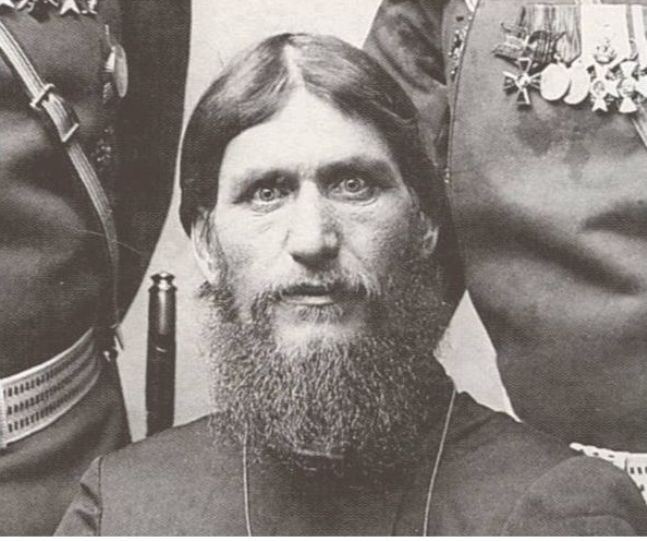

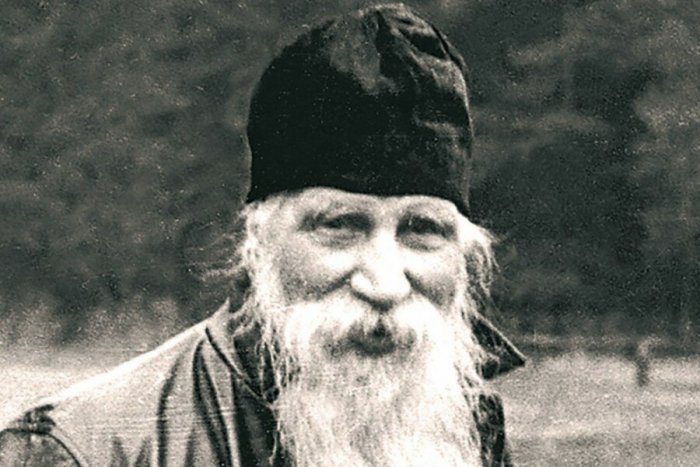

In a review sent to clients last week called “Doomsday Risk” (available to RBC), BCA Research Chief Strategist Peter Berezin, a former Goldman Sachs economist, asks a non-trivial question for investment analysis: can the end of the world come and what is the probability of the total death of human civilization .

Although such a hypothetical event is considered to be a so-called “tail risk” (tail risk), implying an extremely low probability, it should not be underestimated. “Most disappointingly, our analysis suggests a high probability of extinction of people on the horizon of several centuries, and possibly much earlier,” the review says.

Recognizing that the calculation of such probabilities is just a game of the mind, Berezin nevertheless estimates that the probability of the death of mankind by 2290 is 50% and that this will happen by 2710 at 95%.

“Great Filter”

The emergence of intelligent life on Earth was in itself a rare event – otherwise, people could count on finding at least some traces of their own kind among the 400 billion galaxies of the observable Universe. However, there are still no signs of the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations, Berezin argues.

The American scientist Robert Hanson in 1996 explained this with the help of the Great Filter concept, which, among other things, implies a high probability of self-destruction of humanity at the stage of advanced technological development. “We already have the technology to destroy the Earth, but we have not yet developed the technology that will allow us to survive in the event of a catastrophe,” writes BCA Research.

Berezin gives an example: in 2012, scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the United States showed that it was relatively easy to breed a new strain of influenza, more dangerous than the “Spanish flu”, which killed 50 million people around the world in 1918. And this is not to mention the threat of nuclear war, an asteroid strike, a pandemic, the emergence of malevolent artificial intelligence, climate change that has gone out of control.

End of the world theorem

Berezin also recalls another well-known catastrophic hypothesis – the “doomsday argument” by astrophysicist Brandon Carter. Carter reasoned that if the people of today are in a random place in the entire human chronology, the chances are good that we live somewhere in the middle of this chronological scale.

The BCA Research economist borrows this idea and assumes that by now, roughly 100 billion people have lived on Earth. If civilization really is destined to perish, it will happen after another 100 billion people are born on the planet.

If humanity can populate other planets or create giant orbital ships, the likelihood of the disappearance of earthly life due to some kind of cataclysm will decrease dramatically, Berezin argues, but at the moment the probability of the end of the world is much higher than it was in the distant past or will be in the future.

According to him, civilization, apparently, has approached a turning point – the third in its entire history, overcoming which humanity will be able to rapidly increase the level of IQ thanks to genetic technologies. Developing intelligence, in turn, will ensure the emergence of more and more intelligent people. However, with increasing opportunities, the risks of the end also increase, the economist argues, referring to the doomsday theorem.

The “end of the world theorem” does not say that humanity cannot or will not exist forever. It also does not set an upper limit on the number of people who will ever exist, nor a date for the extinction of mankind. According to one calculation (Canadian philosopher John Leslie), there is a 95% chance that humanity will perish within 9120 years.

But Peter Berezin suggests that the end of the world could come much sooner. In his analysis, he proceeds from the fact that the total fertility rate in the world will stabilize at the level of 3.0 (now it is about 2.4), and comes to estimates that with a probability of 50–95%, the death of mankind will come before the year 3000.

Investment “ideas”

According to Berezin, if we assume that humanity will die in the foreseeable future, the accumulation of funds ceases to be so attractive. A lower savings rate, in turn, implies a higher interest rate and therefore cheaper bonds, the economist argues.

Another hypothesis that Berezin analyzes in order to influence the choice of investment strategy is the concept of “parallel universes”, in each of which the same laws of nature operate and which are characterized by the same world constants, but which are in different states. Proponents of this idea, including such famous physicists as Stephen Hawking, Brian Greene and Michio Kaku, admit that we live in a multiverse, which consists of many “bubble universes”.

If an investor believes in the multiverse, he may be more prone to bets that can bring a big win with a very small probability, while avoiding very small risks of big losses, argues Berezin. The fact is that when choosing an investment, a person may take into account the fact that even if he himself does not earn a lot of money on it, he will be consoled by the thought that one of his “twins” in a distant galaxy or other quantum state will succeed.

Therefore, if we assume that there are billions of parallel universes where billions of “versions” of each person live, then riskier assets (such as stocks) are preferable for investors to less risky ones (bonds), the BCA Research economist summarizes.